made in France | ANNOTATIONS

Maria Pergay: Master of Stainless Steel

After designing objects and furniture in silver for over a decade, in 1967 Maria embraced stainless steel, an unconventional, new material that soon became her trademark. Gérard Martel of Ugine-Gueugnon, France’s leading steel manufacturer, first introduced her to the metal, the third to so serendipitously capture her interest. In the spring of 1967, he paid her a visit and asked if she would consider fabricating in Uginox, the company’s brand of stainless steel, the small objects and accessories for which she by then had become well known. He even offered to provide the industrial material, quite expensive at the time, free of charge. Martel, a savvy businessman, was interested in cultivating an untapped market. Maria informed him that stainless steel could not possibly be used for making things on such an intimate scale, and “technically speaking they would not be beautiful.” At the same time, she revealed that she had certain ideas for furnishings, and Monsieur Martel immediately encouraged her to try and realize them. Determined to stimulate interest in the use of Uginox in interior design and decorating, he extended the same invitation to other designers, like Michel Boyer, Jacques Charpentier, Françoise Sée, and François Monnet, all of whom accepted the proposition. Boyer, for instance, created his famous X Stool with a stainless-steel base, and Sée designed a low, rectangular cabinet sided in triangular steel panels, those on the front being in relief.

Even though stainless steel had been invented in 1913 and first came into vogue in Art Deco art and architecture of the twenties and thirties— the shimmering exterior crown of New York City’s Chrysler Building (1930) is perhaps the most celebrated example — it was only in the late 1960s that designers came to recognize its aesthetic possibilities for interiors. Maria attributes this shift to the common sensitivity that unites all artists living in the same era: “I believe all creators have a wire attached to a collective subconscious. That is the reason that all of these things happen all over the world without talking and are more or less successful at the same time. I am only the ouvrier [laborer] of ideas, that’s all. I’m more like a radio catching some lines, some ideas, some volumes, and I ask some wonderful people to execute them.” In 1967, around the time that Monsieur Martel approached Maria and her contemporaries, Jean Coural, general administrator of the French Mobilier National, a state agency that oversees the furnishings in government buildings like the presidential Palais de l’Élysée and foreign embassies, commissioned Joseph-André Motte to design a desk in stainless steel for the prefecture of the Val d’Oise, just outside Paris. (He had previously created a stainless-steel chair, which was exhibited at the 1963 Salon des Artistes Décorateurs.1) With an ebony blockboard core covered in stainless steel, Motte’s bureau was above all a modern looking, functional object of quality, designed expressly for serial production. When faced with fabricating the prototype, artisans in the Atelier de Recherche et de Creation of the Mobilier National were obliged to devise special tools in order to shape the material; their traditional cabinetmaker’s utensils were not durable enough.2 Uginox, the stainless steel division of Ugine-Gueugnon, manufactured the desk as well as the stainless-steel creations of Francoise Sée for Ramsay, Michel Boyer for his Galerie Rouve, Francois Monnet for Kappa, and Maria’s early ventures into the new medium.

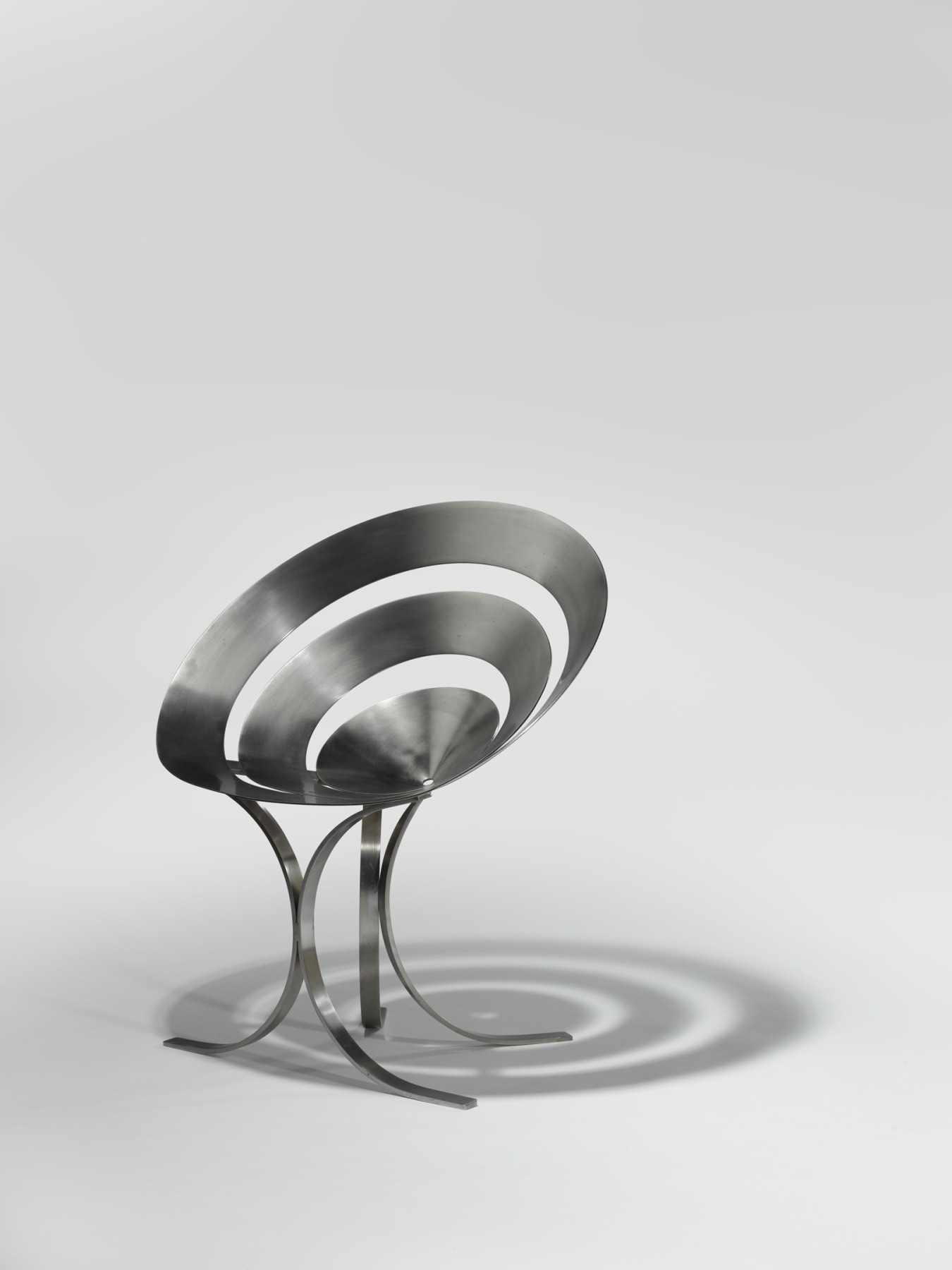

Maria Pergay, Chaise Anneaux / Ring Chair, 1968

The first piece Maria designed in Uginox stainless steel was none other than her famed Flying Carpet daybed (1967–68). She remembers being surprised with the stunning results of her initial endeavor in steel. A tribute to her fascination with reverie, the piece, with its undulating line, also resonates with the utopian spirit of the late 1960s, an era when creators freely combined ideas of fantasy and function in their work. At the end of the 1960s, the artist Georges Mathieu visited 2 Place des Vosges, and the Flying Carpet daybed instantly captivated him. “Madame, who made this?” he inquired. After Maria answered, Mathieu retorted, “Madame, if I had made this bed, the entire world would know it.” The flamboyant painter probably recognized a sensuality in Maria’s bed similar to that in his own gestural canvases of Lyrical Abstraction. Following her Flying Carpet daybed, Maria designed her iconic Ring chair (1967–68). Composed of three concentric sheets of stainless steel, the effect is one of a spiral or a circular target with a bull’s-eye for the seat. Maria recalls that the idea for this object sprang to mind while she was peeling an orange. In addition to the Flying Carpet daybed and the Ring chair, her first stainless-steel collection also comprised, among other pieces, the Wave desk, its top resting on an L-shaped support and sporting the same serpentine form as the daybed, an oval dining table with an unusual carved out base, a magazine rack resembling a giant envelope, and a low table with three round surfaces, one in copper and the others in steel, that fanned out one on top of the other around a central stem. All these works displayed elegant, platinum-like sheens and unblemished surfaces with no visible seams or joints. Bending and cutting stainless steel of this thickness and on this scale without the assistance of lasers or other specialized equipment, neither of which existed at the time, while maintaining immaculate finishes was virtually unheard of during this epoch. Even if other designers already had made furniture in stainless steel, Maria was the first to treat it as a refined material and exploit its inherent beauty. Functional furnishings of impeccable aesthetic rigor, these early stainless-steel pieces set the standard for her future designs.

Despite the sudden popularity of stainless steel among contemporary designers in the late 1960s, Maria’s work stood out. First and foremost, she was completely dedicated to the material, stating “copper is too fragile, aluminum too light, gold too symbolic, silver too weak, bronze is out of fashion, and platinum inaccessible. The exchanges with them don’t work. You can always polish and re-polish. Steel resists and is unforgiving. If what you do to it doesn’t work, you can’t hide it. The work immediately reveals its flaws. Nothing is more beautiful than steel.” Even after completing her first collection, Maria rarely strayed from her new medium. Boyer and Charpentier, in contrast, never demonstrated any specific fidelity to steel. They often combined it with other materials, like leather and glass, or discarded it entirely, choosing instead to experiment with lacquer and Formica. Boyer’s steel works in particular were far stricter and more sober than Maria’s, favoring hard, straight lines and technical joins, just what one would expect with such a metal. Maria sought instead to tame stainless steel and directed her artisans to ply and re-ply entire sheets of it, until she obtained the precise, often fantastic forms she envisioned in her imagination — undulating curves, ovals, spirals. She also began to juxtapose different types of steel in the same piece, placing polished sections next to matte ones to produce a marquetry like effect. This technique eventually became another of Maria’s trademarks and signified her treatment of stainless steel like an exotic wood or precious metal.

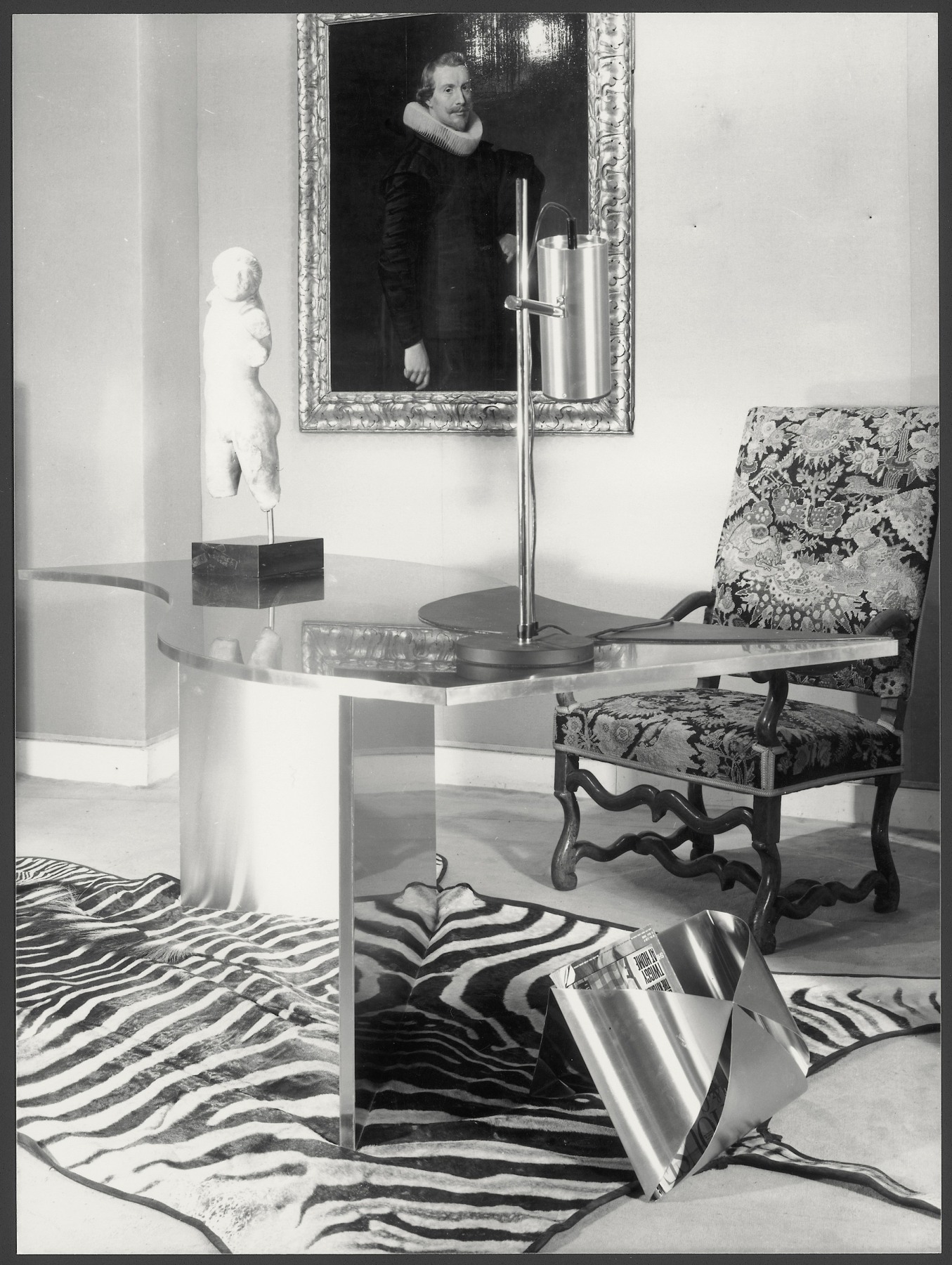

Wave Desk & Magazine Rack exhibited at Galerie Maison et Jardin, Paris, May 1968

On 13 May 1968, in the midst of heated student uprisings in Paris, Jean Dive unveiled a radically forward-thinking idea in interior design at the showroom of Galerie Maison et Jardin, a high-end boutique on Boulevard Saint-Germain for which he worked as head decorator. Enchanted by the power and innovation of Maria’s stainless-steel collection, he assembled various décors in which her furnishings were prominently featured alongside antiques, old master paintings, and contemporary artworks of distinguished quality and provenance. In an exposé on the exhibition, Maison Française pronounced stainless steel the “material of the future.”3 “Stainless steel has proven itself,” the magazine conceded. “Its qualities of resistance are surprising: absolute solidity, stability…. Employed skillfully with beautiful antique elements, it offers new possibilities for the mixing of styles that remains a form of decoration dear to those who desire to adapt to their lives today certain precious elements of the past.” Gilles Sermadiras, director of Galerie Maison et Jardin, declared in the same article that stainless steel was “the material that goes best with modern life.” Plaisir de France, in a pendant exposé on the exhibition, acknowledged the metal to be “rich enough in itself to represent the contemporary” and recognized Dive’s presentation as an answer to a lingering malaise in taste of the period: “Some laugh about it, others cry: Our era has not been successful in imposing its style. Unsettled when it comes to home décor…the general public—although showing more interest than it usually has—hesitates between the admiration for reassuring centuries past and the legitimate desire it feels to live within its own time.”4 Because “a greater and greater number of decorators” were treating steel furniture “as works of art, giving them a place of honor in rooms,” Plaisir de France assured readers that such a “noble” material could “be placed alongside the most beautiful woods, old master paintings, priceless collections, fabrics, and carpets.” Even the popular weekly magazine L’Express took note of the exhibition and the unique possibilities of Maria’s preferred medium: “We are only beginning to understand stainless steel, to bend it, to polish it; decorators must become familiar with the material…learn to combine stainless steel with wood, glass, copper, know how to tone down the sharpness of its edges, to give a style in the end to the ensemble.”5

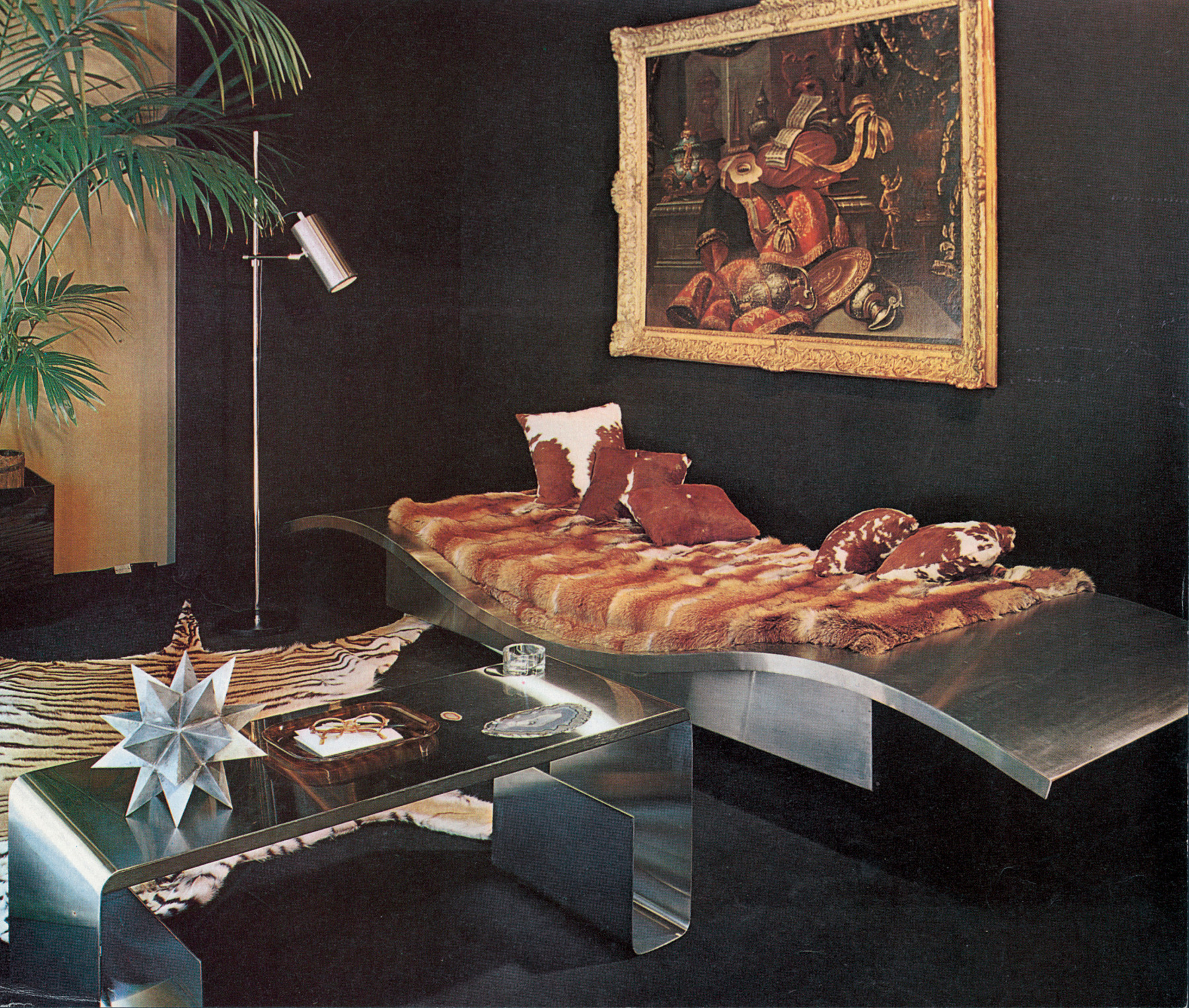

Flying Carpet Daybed and stainless-steel and amethyst low table at the Galerie Maison et Jardin in an exhibition organized by Jean Dive, Paris, May 1968, reproduced in Plaisir de France, January 1969.

Dive divided the space of Galerie Maison et Jardin into different rooms, nearly all of which included Maria’s work. In the boutique’s window, he installed a salon to display her Flying Carpet daybed, which fulfilled “the function of couch, meridienne, chaise longue” (Plaisir de France) with “the fluidity of its form” making one “forget it’s of steel” (Maison Française). “The stainless steel of A Thousand and One Nights? Why not?” Maria inquired. “Why not make it gentle, friendly, peaceful?” Above this “Oriental fairytale for the interplanetary age” (L’Express) hung an “orgiastic” (Maison Française) seventeenth-century still-life painting against a wall of black baize. Several goat-hide pillows accented the red fox–fur bedcover. While the latter was Maria’s idea, she did not much care for the former. Flanking a tiger pelt across from the daybed stood a low table by Maria with rounded edges, amethyst inlays, and turned-up, J-shaped feet.

The Wave desk, with a lozenge of imbedded black leather delimiting the work area, was the centerpiece of the masculine office-library, its sinuous curves echoing those of the Louis XIII armchair as well as the wavy stripes of the zebra skin lying on the floor. A seventeenth century portrait of a Dutchman decorated the wall, an African wood sculpture of an antelope’s head animated the desktop, and Maria’s magazine rack leaned on the floor. Stainless steel shelves in the form of individual opened and closed cubes, also Maria’s creation, were stacked against a wall, offering “a great liberty of composition” (Plaisir de France). In the dining room’s “very rich décor…steel is the calm note, necessary for the appetite” (Maison Française). Her oval table, “cut like a sculpture” (Maison Française) and reminiscent of a “ring of Saturn” (L’Express), dominated the room. Encircled by caned Regency chairs, it featured a detachable, oval stainless-steel centerpiece for fruit or flowers, also by Maria. At the back of the room, an eighteenth-century Spanish cabinet sat atop an ancient Catalonian side table. Disc-shaped steel sconces with quartz fixtures, Maria’s modern interpretation of traditional candle or gas wall brackets, framed an eighteenth-century Venetian marble bust. A fourteenth-century flora tapestry hanging on the opposite wall completed the ensemble.

Finally, Dive presented a student’s room in which a modest, angular desk and a kidney shaped trash bin, both Maria’s designs, were exhibited. “Maria Pergay has, this time, bent steel just as she likes to — desk and wastepaper basket seem wrapped around themselves” (Maison Française). While she fashioned the desktop, the left flank, and base from a single sheet of steel, the stalk-like support stretching upward on the right side doubled as a reading light. A wooden Louis XIII stool and a small Polynesian figurine counterbalanced the room’s contemporary feel. Looking back on these extraordinary décors at Galerie Maison et Jardin, Maria states: “My congratulations to Jean Dive. This exhibition was the beginning of modernism at Maison et Jardin.”

Saturn Table shown at Galerie Maison et Jardin, Paris, May 1968

All of Jean Dive’s installations emphasized both the preciousness and power of Maria’s contemporary stainless-steel creations in the midst of equally strong, alluring antiques and architecture. Even though she had explored this same tension in her exhibition at Galerie Stella Saint John in the late 1950s, Dive and Galerie Maison et Jardin popularized the style. Like Maison Jansen, Galerie Maison et Jardin wielded enormous influence on French interior decoration of the period. Its promotion and support of Maria’s work through this exhibition as well as numerous subsequent advertising campaigns in well-known art and décor publications, like Plaisir de France, Maison et Jardin, and L’Oeil, dramatically increased her visibility. The alliance Dive forged between the contemporary, as represented in Maria’s designs and those of some of her contemporaries, and the classical was unprecedented and came to define a new refined if eclectic taste popular among younger, wealthier clients searching to integrate something modern into already immaculately furnished interiors.

Following his visit to the Galerie Maison et Jardin exhibition, fashion designer Pierre Cardin, for instance, immediately bought one of every one of Maria’s stainless-steel pieces. (He previously had acquired a silver rooster by her.) He had long been an avid collector of Art Nouveau objects and furnishings, and this purchase may well have marked his initial foray into contemporary design. Furthermore, in a 1972 article on an interior Dive redecorated for a private client and in which he included a dining table by Maria, L’Oeil singled out this juxtaposition of old and new with approval. The ambiance of the predominately white décor “was obtained thanks to a play between subtle modulations in tonalities, discrete variations in textures or materials, and lastly the fortunate distribution of contemporary works and precious antique objects in a perfectly harmonious space.”6

Table Éventail / Triple-tiered Table in stainless steel and copper shown at Galerie Maison et Jardin, Paris, May 1968.

Maria ascribes the evolution in taste that Dive instigated to a generational shift. “Old people died. They gave their houses, furniture, and their possessions to their children. Young people no longer wanted the bourgeois exclusiveness of Louis XVI furniture. They wanted to blend genres.” The robust sculptural quality of her stainless-steel pieces as well as their impeccable craftsmanship — finishes, for example, were as lush as those of exotic woods — naturally appealed to such sophistication. “It was an exciting period,” Maria remarks. “People were ready to see and live something different. The materials were changing and there were lots of new artists. When you change materials, new artists come. New materials, new artists, new imagination. There was an excitement at a different level. Everyone was doing something different, and we were waiting to see what would come next, and to see what images would be those of the future.” The priorities of many designers also evolved. “It was a completely different point of view from that of the 1960s,” Maria recognizes, “when designers like Pierre Paulin or Olivier Mourgue were dedicated to designing for the masses. Anyone could have an armchair in their home, you see. I wasn’t part of that school. I worked on my furniture, with the aim of providing one-of-a-kind quality.”

As she informed L’Express in 1968: “In the modern city…one must learn to live with steel furnishings. But they also will teach us how to live in a modern fashion. Don’t, therefore, think any more about housework…. No more dreadful surprises: scratches disappear [on steel furnishings]. Dust is invisible on them, and I find it amusing to be able to clean them entirely with water.”7 Maria’s work, in large part, established stainless steel as a principal component of furniture design and interior decoration during the 1970s and retrospectively has become one of the cornerstones of that history. Uginox, for example, published an advertisement for its brand of stainless steel showing Maria’s collection along with the slogan: “L’Acier, ce n’est pas toujours des casseroles” (Steel, It’s Not Always Pots and Pans).8 Other advertisers, most notably clothing companies, produced similar publicity campaigns in which female models were seen donning the latest fashions and posing next to Maria’s furniture. This was a revelation for her: “I began to understand that I was doing something original when I saw stores doing advertisements with my objects in the photographs.”

Applique Ronde / Circle Sconce & Table Tambour Deux Sièges / Tambour Table with Two Seats shown at Galerie Maison et Jardin, Paris, May 1968.

The late 1960s marked a watershed not only in Maria’s career and in the French political and social landscapes, but also in the world of contemporary French design as a whole. The exhibition Les Assises du Siège Contemporain (Seats of the Contemporary Chair), curated by François Mathey at the Musée des Art Décoratifs, symbolized this transition. From 3 May to 29 July, the sizable show, a “considerable event…for the quantity and the quality of hopes it generated,” brought together for the first time hundreds of modern and contemporary chairs, from Thonet, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Mies van der Rohe to Jean Prouvé, Pierre Paulin, and Verner Panton.9 Such a groundbreaking exhibition paved the way for the recognition of otherwise isolated creators whose avant-garde work questioned reigning notions of furniture design. Both individual designers and design collectives, like Atelier A and Atelier ETA 1, interrogated the concepts of modernist design — purity and rigidity — by introducing novel elements — humor, playfulness, innovative materials — into their creations. In essence, they forged a return to representation, completely contradicting the dictum “form ever follows function” preached by Louis Sullivan, the American architect and father of modernism. As French designer François Barré asserted: “This wish to give the object a scientific proof in pure materiality leads to a denial of the reality of the object.”10 Even though Maria never aligned herself with any particular design movement, designers and decorators responded enthusiastically to her stainless-steel work, ensuring her status as one of the period’s most visionary creators.

1 Les Assises du Siège Contemporain (Paris: Musée des Arts décoratifs, 1968), 87.

2 Mobilier National, 1964–2000: 40 Ans de Création (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nation- aux, 2004), 106–07. In 1967, through the auspices of the Mobilier National, Motte also designed a hexagonal, stainless-steel low table for the office of the prefect of Cergy-Pontoise.

3 “L’Âge de l’Acier,” Maison Française, no. 220 (September 1968): 112–15.

4 Anne Fourny, “Un Événement dans le Mobilier contemporain: L’Acier inoxydable,” Plaisir de France, no. 363 (January 1969): 45–47, 49.

5 Frédéric de Towarnicki, “Rien n’est Plus Beau Que l’Acier,” L’Express, no. 882 (13–19 May 1968): 96.

6 “Une Camaïeu de Blancs…Pour l’Appartement d’un Architecte,” L’oeil XXX, no. 205 (November 1972): 59.

7 de Towarnicki, “Rien n’est Plus Beau Que l’Acier,” 96.

8 Cited in Patrick Favardin, “Maria Pergay,” Citizen K International, no. 31 (June 2004): 156.

9 Gilles de Bure, Le Mobilier Français, 1965–1979 (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 1983), p. 36.

10 Cited in ibid., 2.

Excerpt from Maria Pergay: Between Ideas and Design by Suzanne Demisch